Subscribe to the NTA’s Blog and receive updates on the latest blog posts from National Taxpayer Advocate Nina E. Olson. Additional blogs from the National Taxpayer Advocate can be found at www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/blog.

Since the IRS implemented the private debt collection (PDC) initiative last year, I have been concerned that taxpayers whose debts are assigned to private collection agencies (PCAs) will make payments even when they are likely in economic hardship – that is, they are unable to pay their basic living expenses. As discussed in my 2017 Annual Report to Congress, this is exactly what has been happening. The recent returns of approximately 4,100 taxpayers who made payments to the IRS after their debts were assigned to PCAs through September 28, 2017 show:

- 28 percent had incomes below $20,000;

- 19 percent had incomes below the federal poverty level; and

- 44 percent had incomes below 250 percent of the federal poverty level.

As a refresher, the IRS uses 250 percent of the federal poverty level as a proxy for economic hardship in several situations, such as in administering the Federal Payment Levy Program (FPLP). FPLP is an automated system the IRS uses to match its records against those of the government’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service to identify taxpayers with unpaid tax liabilities who receive certain payments from the federal government. IRC § 6331(h) allows the IRS to issue continuous levies for up to 15 percent of federal payments due to these taxpayers who have unpaid federal liabilities. As explained in my 2014 Annual Report to Congress, the IRS excluded Social Security recipients whose incomes were below 250 percent of the federal poverty level after a 2008 TAS research study demonstrated that the FPLP program levied on taxpayers who were experiencing economic hardship.

In 1998, Congress first adopted the measure of 250 percent of the federal poverty level in IRC § 7526 to identify taxpayers who cannot afford representation in IRS disputes and are therefore vulnerable to overreaching by the IRS. The January 2018 Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 adopts the measure to excuse some taxpayers from paying user fees to enter into installment agreements (IAs). Still more recently, the House of Representatives included a provision to exclude taxpayers whose incomes are less than 250 percent of the federal poverty level from referral to a PCA in the bipartisan Taxpayer First Act, H.R. 5444, which passed the House with a recorded vote of 414-0 on April 18, 2018.

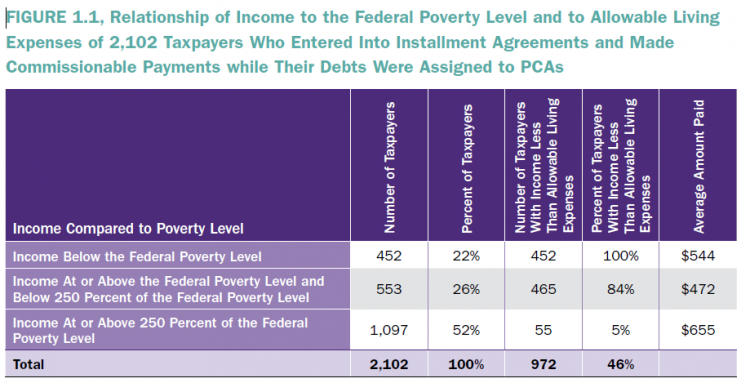

PCAs solicit full payment of the tax debt when they contact taxpayers, and if the taxpayer cannot immediately pay, the PCA can offer an IA. We took a closer look at the IAs taxpayers entered into, and I included in volume 2 of my 2017 Annual Report to Congress a TAS Research Study that reports our findings. Specifically, we studied the financial circumstances of 2,102 taxpayers who, between April 10, 2017 (when the IRS began assigning tax debts to PCAs) and September 28, 2017, entered into an IA while their debts were assigned to a PCA and made a payment on which the PCA received a commission.

All of the IAs set up by the PCAs were “streamlined,” which taxpayers can obtain without submitting financial information. Streamlined IAs can be for up to seven years, depending on the amount the taxpayer owes, as long as the term of the IA is within the statutory period for collection. (We discuss our concerns about allowing PCAs to offer seven-year IAs in my 2016 Annual Report to Congress.)

In addition to looking at these 2,102 taxpayers’ income levels, we checked to see how often their incomes were exceeded by their allowable living expenses (ALEs). ALE standards determine how much money taxpayers need for basic living expenses (for items like housing and utilities, food, transportation, and health care), based on family size and where they live. The IRS compares the taxpayer’s income with ALE standards to determine the taxpayer’s ability to pay his or her tax debt and at what level.

Figure 1.1 shows what we discovered about taxpayers who entered into installment agreements and made payments between April 10, 2017 and September 28, 2017 while their debts were assigned to PCAs.

This pattern of taxpayers whose debts are assigned to PCAs entering into IAs and making payments they appear to be unable to afford is continuing. IRS data shows that since the inception of the program in April 2017 through March 29, 2018, of 9,751 taxpayers who entered into IAs and made payments while their debts were assigned to PCAs:

- 24 percent had incomes below the federal poverty level – all of these taxpayers’ incomes were less than their ALEs;

- 22 percent had incomes at or above the federal poverty level and below 250 percent of the federal poverty level; 80 percent of these taxpayers’ incomes were less than their ALES; and

- Overall, 43 percent who entered into IAs had incomes less than their ALEs.

On April 23, 2018, I issued a Taxpayer Advocate Directive (TAD) ordering the IRS not to assign to PCAs the debt of any taxpayer whose income was less than 250 percent of the federal poverty level. I ordered the IRS to respond to the TAD, either by agreeing or by appealing the TAD to the Deputy Director for Services and Enforcement by June 25, 2018.

In the meantime, as the second quarter of fiscal year 2018 drew to a close, we continued to gather data about how taxpayers are faring in the hands of PCAs. With the PDC program more than a year old, we think it’s time to find out how often taxpayers default on IAs they enter into while their debts are assigned to PCAs. We plan to report our findings in my Fiscal Year 2019 Objectives Report to Congress, which will be published later this month.

The views expressed in this blog are solely those of the National Taxpayer Advocate. The National Taxpayer Advocate is appointed by the Secretary of the Treasury and reports to the Commissioner of Internal Revenue. However, the National Taxpayer Advocate presents an independent taxpayer perspective that does not necessarily reflect the position of the IRS, the Treasury Department, or the Office of Management and Budget.

Source: taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov

Leave a Reply