Subscribe to the NTA’s Blog and receive updates on the latest blog posts from National Taxpayer Advocate Nina E. Olson. Additional blogs from the National Taxpayer Advocate can be found at www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/blog.

My June Report to Congress included an Area of Focus entitled: “The IRS Has Expanded Its Math Error Authority, Reducing Due Process for Vulnerable Taxpayers, Without Legislation and Without Seeking Public Comments.” The post-processing math error issue came up after a report by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) said the IRS improperly paid refundable credits, including the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), to those filing 2016 returns with taxpayer identification numbers (TINs) (e.g., Social Security Numbers) that were issued after the due date of the returns. TINs are long strings of numbers that can easily contain typos. The IRS committed to “evaluate this population for inclusion in the appropriate post-refund treatment program.” Perhaps because it costs $1.50 to resolve an erroneous EITC claim using automated math error authority (MEA) compared to $278 for an audit (according to TIGTA), the Wage and Investment Division (W&I) planned to use MEA to recover these credits in 2018.

I asked Counsel about the legality of using MEA to disallow credits long after the IRS had processed the returns (i.e., post-processing) and paid them. Counsel responded on April 10, 2018, with a Program Manager Technical Advice (PMTA) that approved the practice (here). It concluded there were no due process concerns. This blog explores the due process that the government may be constitutionally required to provide before recovering EITC from those who depend on it to survive.

Those Who File Returns to Obtain Benefits to Survive Are Probably Entitled to More Due Process Than Those Who File Returns to Pay Taxes

The EITC is a refundable tax credit that has become one of the government’s largest means-tested anti-poverty programs for the working poor. It lifted 27 million eligible workers and families out of poverty or made them less poor in 2017, according to the IRS.

Automated enforcement procedures are ill-suited for recovering EITC from vulnerable taxpayers who need it to survive. When an automated system spits out a confusing math error letter that proposes to deny the EITC (as described in my 2014 Report), the addressee may be less likely to receive the letter than middle-class taxpayers, for example, because he or she moves frequently. Even if the addressee receives the letter, he or she may be less likely to understand it due to language barriers, illiteracy, or a lack of access to technology or assistance from a tax professional. Moreover, unlike audits using deficiency procedures, the IRS sends fewer letters (i.e., one math error notice vs. three or more letters from exam), with shorter deadlines (i.e., 60 days vs. more than 120 days in an exam) when it uses MEA. These challenges may prevent EITC recipients from providing the type of response needed to retain the EITC or to obtain a hearing before the Tax Court. Thus, even regular math error procedures can erroneously deprive EITC recipients of the means to live.

Due Process Requires Pre-Deprivation Judicial Review Before Terminating Welfare Benefits

The same concerns that I have about the IRS’s automated recovery of EITC benefits led the Supreme Court to hold in Goldberg v. Kelly in 1970 that due process requires the government to provide a particular type of hearing to welfare recipients before terminating their benefits. The hearing must permit them to appear personally with or without counsel before the decision-making official and to confront or cross-examine adverse witnesses. The Court explained this is because the hearing must be “tailored to the capacities and circumstances of those who are to be heard,” and “written submissions are an unrealistic option for most [welfare] recipients, who lack the educational attainment necessary to write effectively and who cannot obtain professional assistance.”

Moreover, the Court held that a post-termination hearing was not sufficient. It explained the “termination of aid pending resolution of a controversy over eligibility may deprive an eligible recipient of the very means by which to live while he waits.” The Court elaborated that “this situation becomes immediately desperate. His need to concentrate upon finding the means for daily subsistence, in turn, adversely affects his ability to seek redress from the welfare bureaucracy.” This analysis suggests that due process requires more when the government recovers the EITC, than when it collects taxes (as noted here by Megan Newman in 2011).

The IRS might argue that the filing of a tax return is the application for EITC because each year stands alone in the tax system. Thus, the use of regular math error to disallow an EITC claim before it has been paid may be more analogous to denying a welfare application than to terminating welfare benefits. However, the use of retroactive post-processing MEA to recover EITC that the IRS has paid seems more analogous to the termination of welfare benefits. As with the termination of welfare benefits, using retroactive MEA to recover EITC that has been paid poses a more significant risk that the taxpayer will be deprived of the means to live and to challenge the determination.

Because the “Existence of Government” Once Trumped Due Process, Tax Collection Was Permitted – and Continues to be Permitted – Before Judicial Review

Notwithstanding Goldberg v. Kelly, the idea that due process might require that the government provide a pre-deprivation hearing in court before collecting tax sounds like heresy to some. As I discussed in my Griswold lecture several years ago, the perceived wisdom is based on several early Supreme Court cases such as Springer v. United States in 1880, in Dodge v. Osborn in 1916 and in Phillips v. Comm’r in 1931, all of which held that postponing judicial review of a tax liability until after it was collected did not violate due process, though these cases all involved wealthy taxpayers.

In Springer the Court reasoned that if every taxpayer could sue before paying, the very “existence of [a] government” could be at stake. This statement probably needed little explanation at the time. In the 1700s the perception that sympathetic local juries in America were refusing to be impartial in customs disputes led the British Parliament to shift revenue litigation to courts sitting without juries (as recently described by Eleventh Circuit Judge Pryor’s concurring opinion in United States v. Stein). The federal government had defaulted on its debt obligations in 1790, and between 1873 and 1884, ten states were defaulting (as discussed here). Indeed, the taxpayer in Springer had refused to pay the income tax, arguing before a jury in a district court that it was unconstitutional, and had appealed the decision to the Supreme Court after the government tried to collect. Although this sounds frivolous today, in 1895 in Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., the Supreme Court held that portions of the income tax were unconstitutional.

Moreover, a lot fewer suits would have been needed to threaten the existence of government before the turn of the century when the tax base was narrower. Before 1942, the government collected more in excise taxes than in either individual or corporate income taxes (according to OMB historical Table 2.2). In 1895 only the rich paid income taxes, as those with less than $4,000 in income were exempt (i.e., over $102,000 in today’s dollars, as described in Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co. and updated for inflation going back to 1913 using the BLS inflation calculator). [For further discussion of the evolution of the income tax see a study in my 2011 report here.]

Later decisions generally cited the earlier ones without revisiting the analysis. For example, in 1974 the Court held in Bob Jones Univ. v. Simon that an entity’s tax-exemption could be revoked without a pre-deprivation hearing, provided it was given a post-deprivation hearing. Thus, although the assumptions underlying these cases were never closely reexamined (as described in my Griswold lecture and here by Leslie Book) it is common knowledge that taxpayers do not have a constitutional right to an in-person pre-deprivation hearing before a court.

The Amount of Process that Is Due Depends on Balancing the Interests of the Government and the Individual

As the Supreme Court explained in 1976 in Mathews v. Eldridge, however, due process “is flexible and calls for such procedural protections as the particular situation demands.” According to the Court, the timing and sufficiency of the hearing depend upon:

1. the private interest that will be affected by the official action;

2. the risk of an erroneous deprivation of such interest through the procedures used, and probable value, if any, of additional procedural safeguards; and

3. the Government’s interest, including the function involved and the fiscal and administrative burdens that the additional or substitute procedures would entail.

The Balance Has Shifted

Today’s EITC was enacted as part of the Tax Reduction Act of 1975, long after the Supreme Court first concluded that taxpayers had no right to a pre-deprivation hearing.

Moreover, the existence of government is no longer at risk (as discussed below). Thus, if the Mathews factors were applied today, a court might determine that due process requires the government to provide EITC recipients with something more than post-deprivation judicial review.

First, the private interest that will be affected by recovering the EITC seems more like welfare benefits – the same private interest that was at stake in Goldberg v. Kelly – than a tax.

Second, while MEA was once used only for arithmetic errors, which present a low risk of erroneous deprivation, those risks have increased as the authority has been used more broadly. It can now be used for clerical errors, and the Treasury has proposed to expand it even further. (I discuss my concerns in the 2017 Purplebook). Once we depart from using MEA for clear-cut error detection, the risk of an erroneous deprivation is higher, especially for EITC claimants who may have the types of communication challenges discussed in Goldberg v. Kelly.

Although an incorrect TIN might seem like a clear-cut and reliable way of identifying people who are not eligible for the EITC, that is not what research shows. A 2011 TAS study of math errors triggered by incorrect TINs found that the IRS subsequently reversed them, at least in part, on 55 percent of the returns. The IRS could have resolved 56 percent of these errors on its own (e.g., because a similar TIN was listed for the same dependent on a prior year return). Furthermore, in 41 percent of the cases where the IRS could have corrected the TINs (and in another 11 percent where it could have corrected at least one TIN) without contacting the taxpayer, the taxpayer did not respond and was denied a tax benefit – of $1,274 on average – that he or she was eligible to receive. Moreover, the risk of erroneously depriving eligible taxpayers of EITC increases with post-processing math error procedures, for the reasons described below.

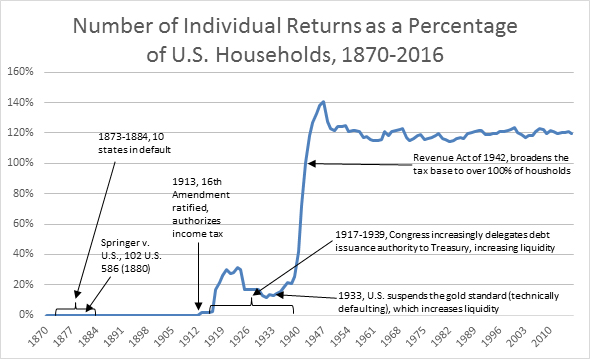

Third, while the government continues to have an interest in avoiding improper EITC payments, risks to the “existence of government” have declined due to a broadening of the tax base and other factors reflected in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Risks to the Existence of Government Declined As It Broadened the Tax Base

[Note: Figure 1 reflects TAS’s analysis of data from the IRS Statistics of Income Division, the U.S. Bureau of the Census, and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (June 2018) (on file with TAS).]

Indeed, Congress implicitly acknowledged that the balance had shifted – with judicial review no longer threatening its existence – by 1924 when it gave taxpayers who receive a notice of deficiency the right to a pre-deprivation hearing before the Board of Tax Appeals (predecessor of the Tax Court) or by 1969 when it strengthened the Tax Court’s independence (as discussed here). If there were any doubt that the balance had shifted, beginning in 1998 Congress provided taxpayers with the right to an independent administrative and judicial review (i.e., a collection due process (CDP) hearing) before the IRS could issue a levy and after it filed a notice of federal tax lien.

[As a side note, when the IRS recovers EITC benefits by offsetting future EITC claims, the taxpayer is not entitled to a CDP hearing. This is a defect in the CDP process, according to Bryan Camp (here). Moreover, Diane Fahey has suggested (here) that CDP hearings might fall short (e.g., because the Appeals adjudicator is not independent), if a pre-deprivation hearing were required under the Constitution. We will be addressing aspects of this issue in my upcoming Annual Report to Congress, which will include a legislative recommendation to increase due process for taxpayers who are shut out of district court and the Court of Federal Claims under the so-called “Flora rule” because they cannot full pay.]

Post-Processing Math Error Procedures Might Fall Short

If a taxpayer receives a math error notice, understands it, and responds timely and appropriately, he or she could obtain a notice of deficiency, which would trigger the right to judicial review before being deprived of the EITC under IRC § 6213. For reasons described in Goldberg v. Kelly, however, these procedural hurdles may prove too burdensome and may even raise due process concerns. Indeed, we know from the example above that math error notices are ineffective in communicating to taxpayers that they have a right to contest the assessment and how to do so because a significant number who were entitled to the EITC failed to respond. Post-processing math error procedures exacerbate these concerns because the IRS’s delay makes it more difficult for taxpayers to:

- discuss the issue with a preparer who could help them respond;

- access underlying documentation to demonstrate eligibility;

- recall and explain relevant facts;

- return any refunds (or endure an offset) without experiencing an economic hardship; and

- learn how to avoid the problem before the next filing season.

For these reasons, I believe the IRS should reconsider its use of post-processing MEA to recover the EITC. It should be looking for ways to help taxpayers validate EITC claims when they are filed. If it must question them later, then it should provide procedures “tailored to the capacities and circumstances” of the EITC recipient, as required by Goldberg v. Kelly. If instead, it continues to expand its MEA, it may find itself defending a not-so-frivolous lawsuit alleging that it is violating an EITC recipient’s constitutional rights.

The views expressed in this blog are solely those of the National Taxpayer Advocate. The National Taxpayer Advocate is appointed by the Secretary of the Treasury and reports to the Commissioner of Internal Revenue. However, the National Taxpayer Advocate presents an independent taxpayer perspective that does not necessarily reflect the position of the IRS, the Treasury Department, or the Office of Management and Budget.

Source: taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov

Leave a Reply